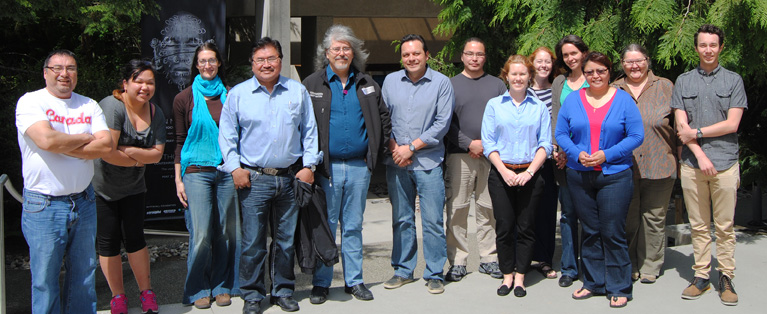

Aboriginal Audio and Digitization Program trainees & MOA staff: (left to right) Roger Patrick, Lake Babine Nation; Michelle George, Tsleil-Waututh Nation; Nadine Hafner, UBCIC; Marvin Williams, Lake Babine Nation; Andrew Bak, Tsawwassen First Nation; Gerry Lawson, MOA; Ryan Dennis, Tahltan Central Council; Bobbie Hembree, Tsleil-Waututh Nation; Alissa Cherry, UBCIC; Judy Thompson, Tahltan Central Council; Pauline Hawkins, Tahltan Central Council; Ann Stevenson, MOA; Aaron Leon, Splatsin Tsm7aksaltn Teaching Centre Society (absent: Rosalie MacDonald, Lake Babine Nation)

MOA, Photo by Michael Wynne

UBC partners work with BC First Nations to enable digitization of valuable recordings

June 20, 2014 – The prospect of First Nations in this province preserving and revitalizing their languages and cultures, including teaching their histories, and in some cases pressing their land claims, is being aided by a unique pilot program led by UBC Library’s Irving K. Barber Learning Centre and the Museum of Anthropology.

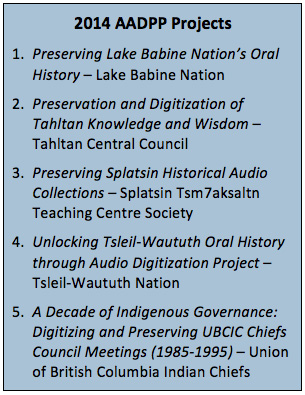

This past April, four First Nations and a provincial First Nations organization were awarded a grant from the Aboriginal Audio Digitization and Preservation Program to assist them in digitizing tape recordings at risk of loss due to age and technological change.

In many cases, the tapes contain valuable recordings of elders speaking their native language and sharing traditional and cultural knowledge.

The five projects (see sidebar) each received $10,000 in matching funds to support training and acquiring special equipment for the work.

Participants from each project received hands-on instruction at the Museum of Anthropology’s Oral History Language Lab, from May 12–16.

“The program is an exciting component of the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre’s Indigitization Program, which enables us to work closely with UBC stakeholders and First Nations partners to build skills and capacity in Aboriginal communities around access and preservation of culturally significant materials,” said Simon Neame, Associate University Librarian and Director of the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre.

“The program is an exciting component of the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre’s Indigitization Program, which enables us to work closely with UBC stakeholders and First Nations partners to build skills and capacity in Aboriginal communities around access and preservation of culturally significant materials,” said Simon Neame, Associate University Librarian and Director of the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre.

‘No better way’

Roger Patrick, a treaty researcher with the Lake Babine Nation in central B.C., attended the training session along with two of his colleagues.

In an interview, he said his office has 1300 tapes stored at the University of Northern British Columbia’s archives.

He described how there is strong community interest in the digitization project, particularly among the youth who are interested in knowing more about their language and culture.

“They are really excited about the information we have,” he said. “(The recordings) are all done in our (Carrier) language—this is what they’re craving for. But firstly we have to digitize them.”

He acknowledged that securing a fluent Carrier speaker to translate the Nation’s recordings is however going be a challenge. Until then, he expects much of the information on them to remain inaccessible to the Nation’s mainly non-Carrier speaking youth, who make up thirty percent of its members.

Furthermore, he worries the language is going to suffer significantly when many of its speakers are gone in 20 years, such that he foresees his nephew who is now in his 40s being the last fluent speaker by then.

Given this, he said there is a desire to see the language preserved and that “there’s no better way than through the digitization project.”

He is also looking for the digitization project to provide answers to questions posed in the treaty process as well as curriculum material for the Nation’s elementary school.

Upon returning home, his team will be sharing with the Nation’s youth the skills gained at MOA in order to help them with their own digitization projects.

Building capacity

Judy Thompson, a language and culture worker with the Tahltan Nation, in northwest B.C., also attended the training session with two co-workers.

In an interview, she said they plan to digitize about 330 audiotapes and that in time more will likely come forward from various family collections.

The tapes include recordings of Na-Dene elders and others who have since passed away, but who were “very knowledgeable about our clan system, songs, dances, plants – lots of different cultural knowledge,” she said.

For example, she told how she has recordings of her grandfather and aunt who lived to be 102 and 101-years old respectively.

Like others, the Tahltan Nation is experiencing the loss of fluent Na-Dene speakers as time passes. As a result, the Nation is focused on revitalizing the language. In that regard, she said the digitization project will contribute to an online Na-Dene dictionary, in addition to school curriculum.

When asked if there were other means to digitize the tapes, apart from the program, she replied that in the past the Nation sent them out of the community, but this was not preferable.

In a subsequent interview, she confirmed that the Nation would rather hold onto its tapes during the digitization process, since they often contain sensitive cultural and personal information. Moreover, she said the Nation wants to develop the ability to do the work itself. Plus she thought families would hesitate to send their personal tapes out of the community.

For these reasons, she reiterated her appreciation for the program’s capacity development approach, which will let the Nation control the digitization process while developing its capability in this area.

The remaining three projects involving the Splatsin First Nation, Tsleil-Waututh Nation and Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs will see thousands of hours of audiotapes being digitized.

‘Tens of thousands’ of tapes

Gerry Lawson, a member of the Heiltsuk First Nation, is MOA’s Oral History Language Lab coordinator and digitization trainer.

In an interview, he recounted how before joining the lab he realized that First Nations in the province, including his own, needed to begin the process of digitizing their at-risk audiotape collections.

As it was, he recalled how his own Nation had “a room full of media on many different obsolete formats—recordings of stories, songs and traditional knowledge in our language that was at risk of becoming inaccessible due to age and equipment obsolescence.”

He estimated that B.C. First Nations have “tens of thousands” of tapes that require digitization.

Regarding the potential value of these recordings, he remarked that there are some in existence from the 1960s and 1970s of elders who intimately understood the first impacts of settlement or industrial development, including life prior to then.

“In terms of their knowledge as children and who they would’ve been exposed to, in this case their elders, you’re talking about really close to contact,” he said. “You’re talking about really authentic information.”

Furthermore, because many spoke a higher or more complex form of their language than what is commonly spoken today, this should significantly benefit language revitalization efforts, he said.

However, he noted there is an urgent need to connect digitization efforts to language and cultural revitalization work underway.

“The fewer fluent speakers that exist the harder it will be to interpret the recordings in support of those programs that seek to teach the language,” he said.

He explained that MOA’s training lab, which he helped to design, has been specifically “geared toward capacity development and addressing the greater landscape of cultural heritage recordings.”

Further aiding the digitization movement among First Nations is a community of practice that is emerging among former and current program participants who are willing to help each other out.

“We’re hoping this spreads,” he said, adding he’d like to see technicians unaffiliated with the program join in anyway in order to get help with their own digitization projects.

Last year, the program awarded inaugural grants to the Tsawwassen First Nation and Upper St’át’imc Language, Culture, and Education Society.

The program, which is supported through yearly funding, will issue its next call for proposals in July 2014.

For more information on the program, visit: www.indigitization.ca.

Page Modified: April 5, 2016